Electro-active Polymers: ShapeShift

I like, kind of have a massive crush on architecture robots. In my spare time I doodle the names of various smoking hot robots in a three-hole punched college-ruled notebook that I store in my TrapperKeeper. And like, every time I see one (a robot, not a TrapperKeeper) I completely freak out and start hysterically screaming, hyperventilating, and crying. Picture the reaction of a typical teenage girl as The Beatles were getting off the airplane in 1964. But to be perfectly clear – I don’t care about robots that are not architecture robots. For instance, I don’t give a semi-ripe fig about the Transformers or that little robot arm with the sad face that works for GM.

Image courtesy www.thekathleenshow.typepad.com

Right now are you asking yourself, “just what exactly IS an architecture robot?” I don’t blame you since I’m pretty sure I just made up the term a few minutes ago. Here’s a definition, which I present to you wholly unencumbered by any process of thought: architecture robots are autonomous building components that can be computer-controlled. If you can think of a better definition (and I bet some of you will) please add it to the comment section. I’d also love to hear about similar projects if you’re working on them.

Image courtesy www.blog.wprb.com

But to return to the main topic of today’s discussion, ShapeShift is ” an experiment in future possibilities of architectural materialization” conducted by the chair for Computer Aided Architectural Design and students studying at the ETH in Zurich in collaboration with the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (EMPA). To put it bluntly, this illustrious group created an “architecture robot.” And yeah, I just fainted a tiny bit at the thought.

Image courtesy http://www.caad-eap.blogspot.com/

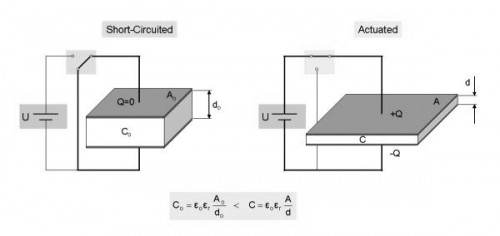

The group’s experiment centered around their work with an electro-active polymer (EAP), “which is a polymer actuator that converts electrical power into mechanical force. In principle it consists of a thin layer of very elastic acrylic tape sandwiched between two electrodes” (ShapeShift). The Shape Shifters, as I have come to call them, took a thin, flexible layer of plastic and attached electrodes to it. And when they ran a few kilovolts through the assembly, the polymer deformed in two directions. The attraction of opposing charges caused the film to squeeze and increase in surface area. Repelling forces between equal charges on both electrodes resulted in a linear expansion of the film, which meant it became thinner.

Images courtesy http://www.caad-eap.blogspot.com/

If you were to pre-stretch the EAP over a bent but highly flexible laser-cut acrylic supporting frame, and you spread carbon black powder over both sides of the component to transport a high voltage across the EAP, and you coated everything with a thin layer of silicon to insulate the electronically charged material, and then you applied electricity to it, then the EAP would expand and the frame would flatten out (ShapeShift). And if you spread peanut butter on one slice of bread and jelly on another and put them together, then you’d have lunch.

Image courtesy www.tastyplanner.com

One of my favorite aspects about these components is that when they are connected to each other they create dynamic self-supporting structures that don’t need any bracing or other static structure to hold them up. The relationship between the pre-streched EAP and its supporting frame is the foundation for the integrity of each component, and each component has an influence on the form and movement of each of its neighbors. That means that the entire dynamic structure can respond to electrical impulses by changing form, and it portends a highly dynamic future for architecture.

[…] Last October I wrote about Shape Shift, the group’s experiment with a electro-active polymers (read more here), and if you enjoyed that project the odds are good that you’ll love what they came up with […]

Leave a Wordpress Comment: